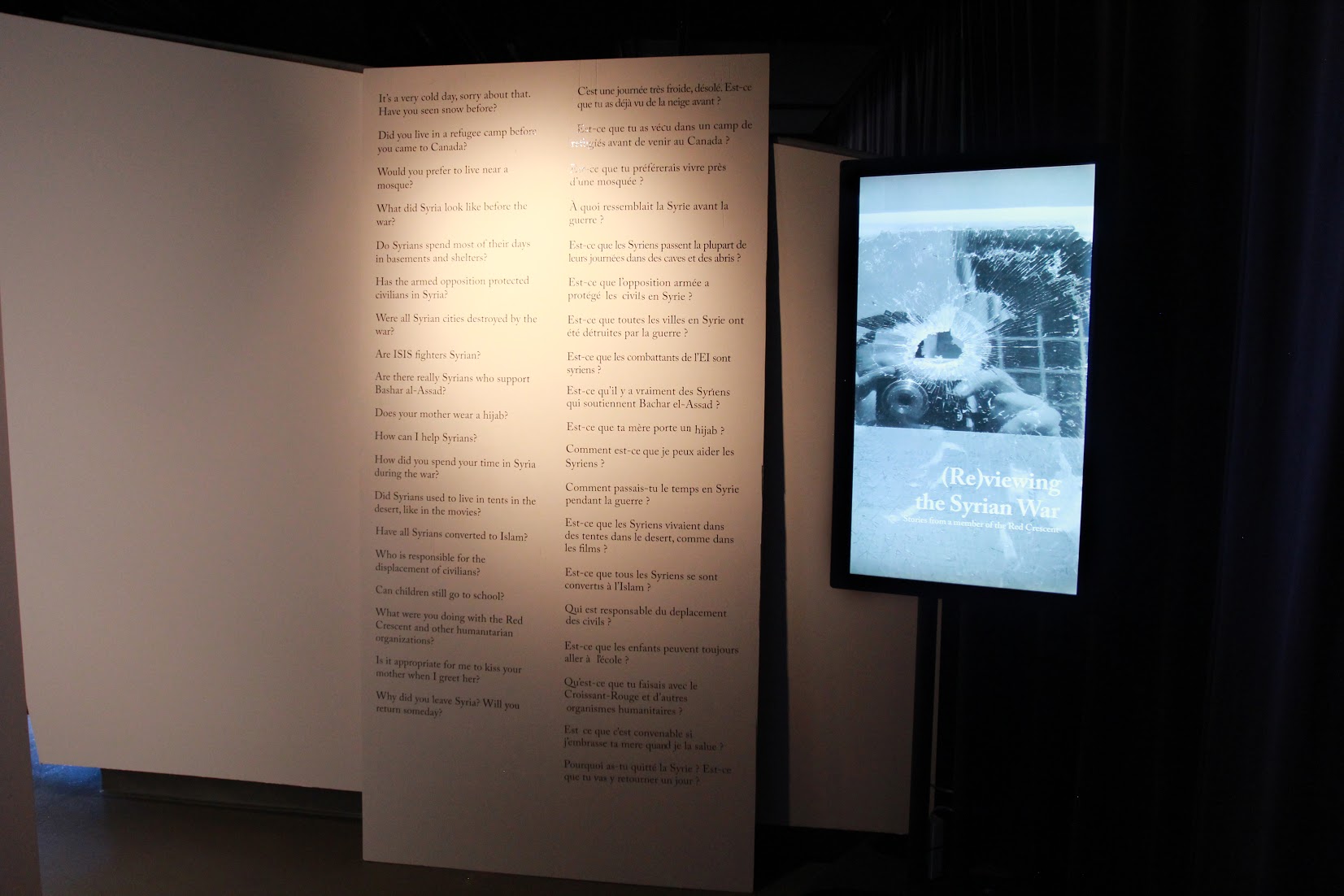

(Re)viewing the Syrian War: Stories from a member of the Red Crescent

The second residency was focused on challenging western media perceptions of the Syrian War through photography and the experiences of a Syrian emergency relief worker and first aid responder, Abood Hamad, who now lives in Montreal. The exhibit took place between November 28 and December 13, 2019, at the Curating and Public Scholarship Lab.

La seconde résidence visait à questionner et défier la perception des médias occidentaux sur la guerre en Syrie, à travers la photographie et l’expérience d’un travailleur humanitaire et secouriste syrien qui vit désormais à Montréal. L’exposition a eu lieu du 28 novembre au 13 décembre 2019, au Curating and Public Scholarship Lab.

Abood Hamad (curator/commissaire):

“Since arriving in Canada I have often been asked about my experiences as a Syrian refugee and humanitarian aid worker. These questions made me realize that the North American media has distorted people’s perceptions of the war and of Syria. I believe that these misconceptions negatively affect our ability to provide support to survivors.

(Re)Viewing the Syrian War addresses some of the questions I have been asked through personal stories and objects, alongside images and videos taken by colleagues, friends, and local observers. The core collection of images was made by Syrian and international photographers, many of whom I met while working for the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC). We each experienced the conflict differently, and each photographer worked in a different context – some for local media, some for personal art projects, some for humanitarian aid organizations – but all with a desire to document the complexities of life in Syria during the conflict. By framing their work with my own stories I hope to shed light on my experiences with SARC in Damascus, Homs, and other parts of the country, as well as after arriving in Montreal two years ago. Ultimately, my goal is to offer a glimpse of how everyday Syrians have lived and responded to the conflict with creativity and resilience.”

«Depuis que je suis arrivée au Canada, on m’a souvent posé des questions sur mon expérience en tant que réfugié et que travailleur humanitaire syrien. Ces questions m’ont fait réaliser que les médias nord-américains avaient faussé la perception qu’ont les gens de la guerre et de la Syrie. Je crois que ces conceptions erronées affectent de façon négative notre capacité à fournir un soutien adéquat aux survivants.

(Re)Voir la guerre en Syrie répond à certaines des questions qui m’ont été posées. Elle le fait à travers des histoires, des objets, des images et des vidéos prises par des collègues, des amis et des observateurs locaux. Le cœur de cet ensemble d’images est l’œuvre de photographes syriens et internationaux, j’ai rencontré un grand nombre d’entre eux lorsque je travaillais pour le Croissant-Rouge arabe syrien (CRAS). Nous avons vécu le conflit différemment, et chacun des photographes travaillait dans un contexte différent, certains pour des médias locaux, certains pour des projets artistiques personnels, d’autres pour des organisations humanitaires. Tous avaient le désir de documenter les complexités de la vie en Syrie pendant le conflit. En contextualisant leurs travaux avec mes propres histoires, j’espère éclairer mon expérience au sein du CRAS à Damas, Homs et d’autres endroits du pays, ainsi qu’après mon arrivée à Montréal il y a deux ans. Ultimement, mon but est d’offrir un aperçu de la manière dont les Syriens ont vécu et réagit au conflit, de manière ingénieuse et avec ténacité.»

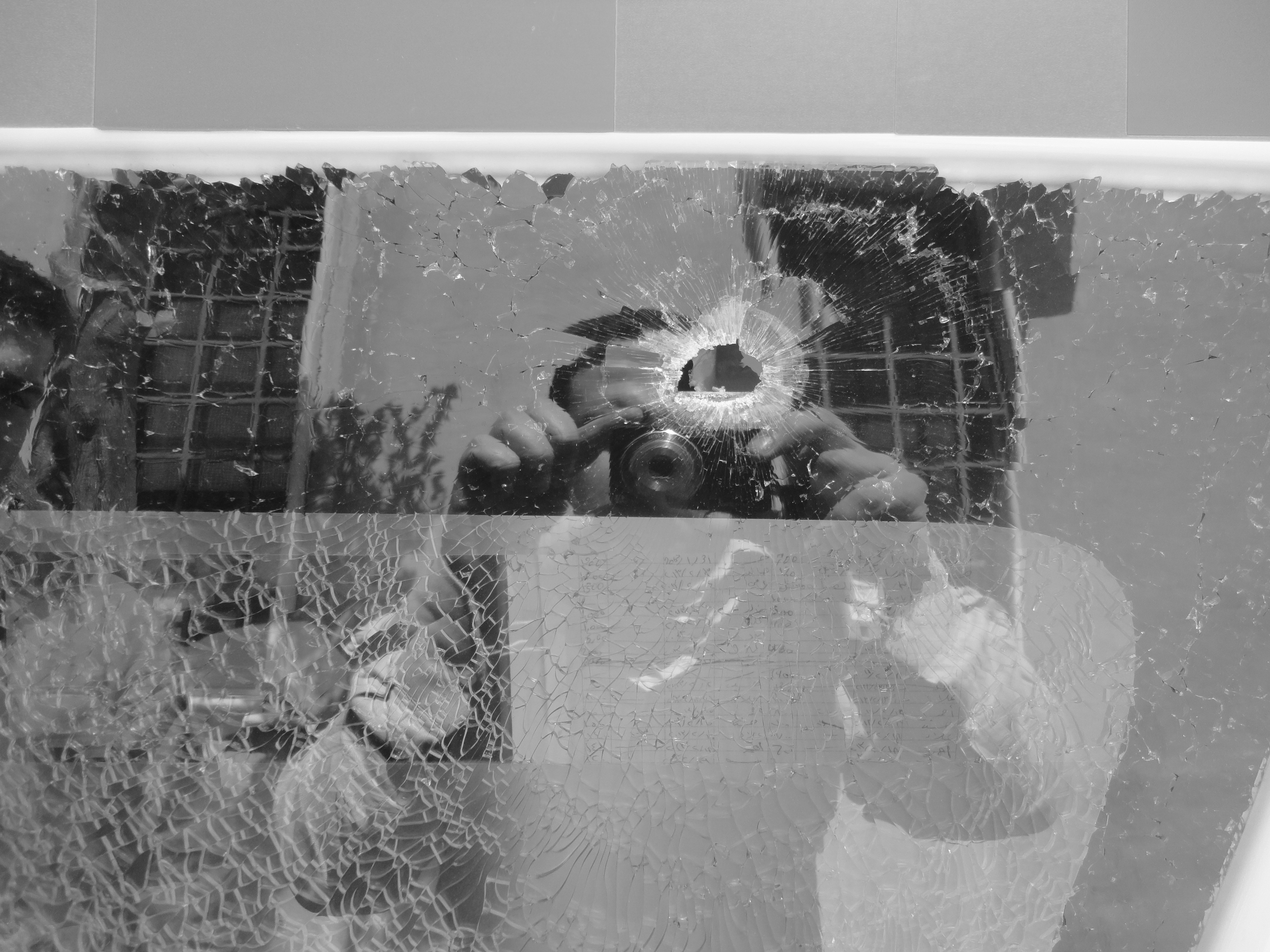

Safety Check. Abood Hamad. Damascus, 2016.

“In 2009, according to the United Nations, Syria had a relatively low homicide rate, quite similar to Canada. This fact may seem unbelievable to some, given that 10 years later Syria ranked as the most dangerous country in the world. Today in Damascus it is routine to check underneath your car before going to work in the morning to make sure no explosives have been placed there overnight.”

«En 2009, d’après le Global Crime and Security Index, la Syrie avait un taux d’homicide relativement bas, assez similaire à celui du Canada. Ce fait peut sembler improbable pour certains, étant donné que dix ans plus tard, la Syrie est classée comme le pays le plus dangereux du monde. Aujourd’hui à Damas, c’est la routine que de vérifier sous sa voiture le matin avant d’aller travailler, afin de s’assurer que personne n’y ait placé une bombe pendant la nuit.»

Screenshot from “Too many blankets”. SARC. Homs, 2015.

“While working with the Red Crescent I was always surprised at how well Syrians were able to adapt to the brutalities of war. Contrary to the images I’ve seen in the Western media showing people utterly paralyzed, waiting in their basements for the war to end, Syrians have created innovative solutions to the challenges imposed by the conflict, and reacted to them in innovative, constructive ways. As a result of the poor coordination of international aid, humanitarian organizations often face a surplus of certain donated items and a scarcity of others. For example, sometimes there were too many blankets, but a shortage of children’s clothing. In response, Abu Samir, a local tailor, used the fabric of donated blankets to sew children’s coats.”

«Quand je travaillais avec le Croissant Rouge, j’étais toujours surpris de la manière dont les Syriens étaient capables de s’adapter aux violences de la guerre. Contrairement aux images que j’ai vues dans les médias occidentaux, qui montraient des personnes complètement paralysées, attendant dans leur cave que la guerre se termine, les Syriens ont trouvé des solutions créatives pour affronter les défis imposés par le conflit. Ils réagissaient à ceux-ci de façon ingénieuse et constructive. À cause de la coordination médiocre de l’aide internationale, les organisations humanitaires font souvent face à un surplus de certains objets et une pénurie d’autres. Par exemple, parfois, il y avait trop de couvertures, mais un manque de vêtements d’enfants. En réponse, Abu Samir, un tailleur local, utilisait le tissu des couvertures reçues pour fabriquer des manteaux d’enfants.»

Selling cotton candy. Mohammed Badra. The official website of the Popular Will Party. Aleppo, 2016.

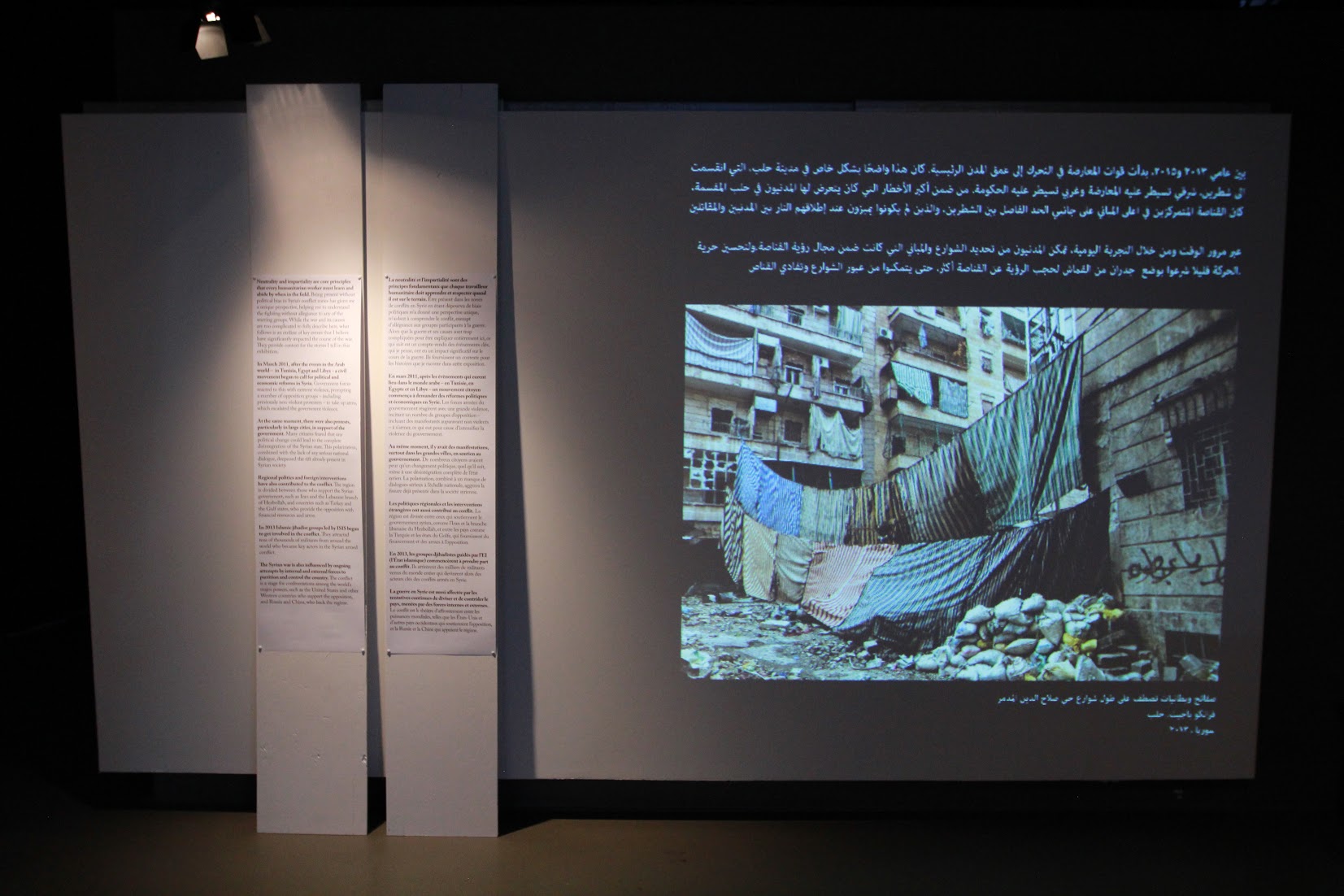

“The Syrian conflict is complex. What began as a clash between anti- and pro-government protestors devolved into a full-scale civil war, with intervention by foreign governments and jihadist militants. While the Syrian government has used violence against non-combatants, at times it has also protected civilian populations. And while many opposition forces defend the rights of the people, these groups have also harmed the communities they claim to protect. There are heroes and villains on both sides, depending on the particular region and moment in the conflict.

My work focuses on the experiences of civilian victims, including humanitarian aid workers who provide assistance in the midst of war. (Re)viewing the Syrian War also encourages visitors to reflect on how they might help, particularly in the case of child survivors. The plight of Syrian children briefly caught the world’s attention in 2015 with a photo of three-year-old Alan Kurdi, who drowned in the Mediterranean Sea while his family was seeking a peaceful place to live. The international community is deeply implicated in this war, so the future of Alan’s generation is the world’s responsibility. When military actions end, the work of repair will have just begun.”

«Le conflit syrien est complexe. Ce qui a commencé comme un désaccord entre les manifestants anti et pro gouvernement a dégénéré en une guerre civile, avec l’intervention de gouvernements étrangers et de militants djihadistes. Alors que le gouvernement syrien a fait usage de la violence à l’encontre de non-combattants, à d’autres moments, il a aussi protégé les civiles. Alors que de nombreuses forces d’opposition ont défendu le droit du peuple, ces groupes ont aussi blessé les communautés qu’elles prétendaient protéger. Il y a des héros et des vilains des deux côtés dans ce conflit, en fonction de la région et la période.

Mon travail se concentre sur l’expérience des victimes civiles, incluant les travailleurs humanitaires qui fournissent de l’aide au milieu de la guerre. (Re)Voir la guerre en Syrie encourage également les visiteurs à réfléchir à la manière dont ils pourraient aider, particulièrement en regard des enfants survivants. La détresse des enfants syriens a capturé brièvement l’attention de la planète en 2015, avec la photo d’Alan Kurdi, âgé de trois ans, qui s’est noyé dans la mer méditerranée alors que sa famille cherchait un endroit paisible pour vivre. La communauté internationale est profondément impliquée dans cette guerre, ainsi, le monde entier est responsable du futur de la génération d’Alan. Quand les actions militaires cesseront, le travail de réparation aura à peine commencé.»

Abood Hamad (curator/commissaire)

Opening of (Re)Viewing the Syrian War at CaPSL

2 Years in Canada: A Conversation about a Syrian-Canadian Friendship, hosted by Abood Hamad and Michael Keeling

Dawson College class visit

Download the exhibition catalogue here.

Téléchargez le catalogue de l’exposition ici.

ReViewing the Syrian War in the news:

The Concordian interview

Credits:

Curator

Abood Hamad

Additional Curatorial Consulting

Maria Juliana Angarita-Bohórquez

SJ Kerr-Lapsley

Lauren Laframboise

Alexandra Nordstrom

Consulting Researcher

Dr. Erica Lehrer

Exhibition Coordinator

Alex Robichaud

Translation + Copyediting

Wathek Alghabra

Nazik Dakkach

Abood Hamad

Anne-Marie Reynaud

Daphnée Yiannaki

Installation Technicians

Michael Eddy

Lex Milton