Blackness and Experience in Two Canadian Establishment Museums: Critical Reflections

By Sally Hough, Research Assistant (Beyond Museum Walls)

How does one experience an establishment museum1? What are the subject positions of people working in and visiting museums? What are the complexities related to inclusion in establishment museums? Can contemporary art disrupt stereotypes of Blackness and Canada’s claim to innocence with regard to race and racism? Museum goers and critical museologists alike are right to be concerned with these questions. On November 23rd, 2018, Dr. Shelley Ruth Butler, a member of the the Beyond Museum Walls research team and a cultural anthropologist with McGill’s Institute for the Study of Canada, gave a guest lecture for Concordia’s “Art and Museum: the Museum Experience” class. The class, taught by Dr. Maya Rae Oppenheimer, aims to understand how a museum impacts its visitors and vice versa by exploring topics such as the politics of museum-going, power dynamics within museum spaces, curatorial strategies, and critical museology. This blog post reviews the lecture as well as presents further commentary and context about the approaches of establishment museums like the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) and the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM).

Dr. Butler’s lecture wove a narrative from the controversial 1989-1990 exhibition “Into the Heart of Africa” at the ROM to the exhibition entitled “Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art,” which showed at the ROM and the MMFA in 2018. “Into the Heart of Africa” was a deeply problematic, ambiguous, and hurtful mix of objects, texts, and artworks exploring Canadian complicity in Africa’s colonization, as well as African cultural aesthetics. It sparked protests outside of the museum, which responded defensively and refused to undertake community consultation. The alienation felt by protestors is well-documented; reading from her ethnography of the controversy, Dr. Butler recalled a protestor’s response to a diorama of an Ovimbundu compound: “It gave you a sad feeling. The hut looked very dark inside like, uh, I don’t know, it was eerie, that’s the word to describe it. A very eerie sort of looking place… It reduced it to something rejectable that you wouldn’t want to claim.” She also showed a short untitled film, created by film students at York University sympathetic to the protestors, which evokes the ROM’s bureaucracy and insensitivity at that time. 2

As Dr. Butler elaborated, both exhibitions presented African art, artefacts, and creations by the Black diaspora. But, the evolution from “Into the Heart of Africa” to “Here We Are, Here” demonstrates how the ROM has increasingly prioritized community dialogue, critical research, consultation, and co-creation with academics and local artists. Since “Into the Heart of Africa,” it has undertaken efforts to improve its collections and exhibits about Africa and the Black diaspora as well as its relationship with the local Black community. For example, the ROM opened a permanent African Gallery in 2008 and in 2013 and Silvia Forni (Curator of African Arts and Cultures, ROM), Julie Crooks (Assistant Curator of Photography, the Art Gallery of Ontario), and Dominique Fontaine (Independent Curator and Founding Director of aPOSteRIORi) launched a multidisciplinary “Of Africa” project to rethink historical and contemporary representations of Africa.3 “Here We Are, Here” marks an important step in this ongoing process. It assembled thought-provoking works depicting individual and collective experiences of Blackness, primarily featuring Toronto artists, although three Montreal artists were added to the MMFA’s iteration. The ROM and the MMFA both made acquisitions subsequent to the exhibition, which is an important indicator of transformation since the process of decolonization must extend beyond exhibitions to address fundamental material issues such as collections. The guest lecture was a fascinating look into the transformation of marginalized pieces in Western galleries, how they have been used to tell various stories, and how they can present their place of origin in different ways.

Last year I was lucky enough to complete an internship under curator Erell Hubert (Curator of Arts of the Americas, Montreal Museum of Fine Art), who at that time was overseeing plans to update its African gallery. My job was primarily to research the pieces in the museum’s collection, write descriptions of their provenance and history and research African art exhibitions around the world as inspiration for the MMFA’s current project of reinstalling its “World Cultures” galleries. I was able to apply my academic background in African Studies to a gallery setting, which was eye-opening and challenging. I learned that despite the best attempts of curators to present foreign artworks and artefacts in an unbiased, historically-accurate, and culturally-sensitive manner, doing so can be difficult amidst donor pressures, budget limitations, and the Western biases that have prevailed in North American museums for decades. Moreover, I learned that the struggle that members of the African diaspora continue to face to be included and honoured in North American settings like academia, healthcare, and the job market are also applicable to art museums.

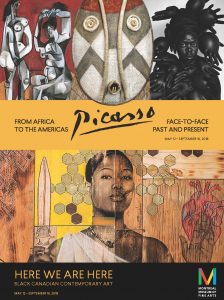

Because of this, it was exciting to see “Here We Are, Here” at the ROM and MMFA. It is still rare for elite museums to feature contemporary Black artists; the ROM’s attempt to showcase local Black artists should be lauded. It must also be noted that in Montreal’s iteration of “Here We Are, Here”, visitors were required to pass through a blockbuster exhibit exploring Picasso and his American, African, and Oceanian influences entitled “From Africa to the Americas: Face-to-Face Picasso, Past and Present” before reaching the exhibition. I was not surprised to find that the MMFA felt compelled to pair “Here We Are, Here” with an exhibition about a famous European painter–it has not completely strayed away from its Eurocentric roots.

Though “Face-to-Face” addressed Picasso’s “appreciation” and appropriation of ‘primitive’ or ‘tribal’ works from Africa, it was not a reversal or overhaul of traditional North American exhibition styles. Furthermore, “Face-to-Face” was far more publicized than “Here We Are, Here,” and many viewers simply felt tired and caught off guard by the time they arrived at “Here We Are, Here.” I personally wish I had been able to take more time in the exhibit but my legs were exhausted by the phenomenon I like to call the ‘museum walk’ and I was not aware that there was a second exhibit to see after Picasso. I only realized that “Here We Are, Here” was on display at the MMFA when I saw posters for it after walking into the museum—even then I did not realize that it was adjacent to “Face-to-Face”! Clearly, “Here We Are, Here” did not get the attention it deserved. Very few reviews were written about it, while “Face-to-Face” was the subject of many. Despite a relative lack of attention on its Montreal iteration, this exhibition destabilized stereotypes of Black Canadians, while at the same time affirming the richness of their contemporary cultural productions, through “personal portraits, memories, emotions, cultural practices, and aesthetics.”4 This is a notable accomplishment given the lack of exhibitions of contemporary African and African diaspora art in Canadian establishment museums.5 Museums like the MMFA and ROM attract large and diverse audiences, which provides opportunities for bold, creative and forward-thinking curation and exhibition.

Learning, dialogue, and cultural exchange, as opposed to racial and cultural tensions, must continue to be a top priority for North American museums and galleries. As I experienced at the MMFA, there is an ongoing effort to do so but it is constrained by factors that have permeated museums for a long time, such as an emphasis on European and North American artists, a preference for ‘Western’ aesthetic styles, and more staff dedicated to the effective display of Western art.

Finally, Dr. Butler’s lecture highlighted how Black artists created both critical and affirmative work in two mainstream museums, pushing towards a more inclusive Canadian history and culture. Black and African artists have contributed immensely to contemporary and historical artistic output, and their inclusion in establishment Western museums demonstrates emerging efforts to re-orient the museum-going experience for all.

- Establishment museums are authoritative institutions, with historical roots in colonial nation-building. Historically, they are associated with the status-quo or dominant ideologies as opposed to experimentation and oppositional voices. The Royal Ontario Museum was established in 1912 and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts was founded in 1860. (S. Butler personal communication).

- One of the student filmmakers Sudz Sutherland, founded Hungry Eyes Media in Toronto with Jen Holness and produced among other films, “Speakers for the Dead“, a film about erasures and denials of Black history in Ontario.

- For further reading, consult “Activism, Objects and Dialogues: Re-engaging African collections at the Royal Ontario Museum”, by Silvia Forni, Julie Crooks, and Dominique Fontaine, in Museum Activism, edited by Robert Janes and Richard Sandell and published by Routledge (2019).

- Shelley Butler, “Travelling Tales: Here We Are Here at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts” in History, Art and Blackness in Canada (working title). Edited by Julie Crooks, Dominique Fontaine, Silvia Forni. Forthcoming.

- For further reading see “Why Have There Been No Great Black Canadian Women Artists,” by Connor Garel, Canadian Art, January 2019 and “Canada’s Galleries Fall Short: The Not-So Great White North,” by Alison Cooley, Amy Luo and Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Canadian Art, April 21, 2015.