Art and Conflict in Ayotzinapa, Mexico

Aurelio Meza

Fall 2017

Excerpts from the essay “Curar saberes difíciles: arte, curaduría y Ayotzinapa.” Calle 14, 12 (21), 2017.

In Winter 2015, Erica Lehrer taught a seminar at Concordia University, Montreal, on the curation of what she and other scholars call “difficult knowledge”—the (usually) violent heritage that cross- or intrasocial conflicts, both past and present, have bequeathed us. An instance of difficult knowledge par excellence, from which many studies in English on the subject derive, is the Shoah or catastrophe, a Hebrew term to refer to the Jewish genocide perpetrated by the Nazi regime. This past is even further problematized by Israel’s current interventionist policy in Palestine, even denying its existence as a country. In this case, as in others just as controversial (like the 50-year long guerrilla in Colombia, or the civil war against drug trafficking in Mexico), it is important to notice that, as Lehrer and Milton say, “curation of difficult knowledge can exacerbate conflict, or keep wounds traumatically open when they might otherwise heal. Yet curating ‘reconciliation’ risks other erasures, neglects, and negations, potentially inflicting further harm by silencing those living with scars, still-open wounds, or ongoing justice.” Difficult knowledge must be named in every possible way, not hidden.

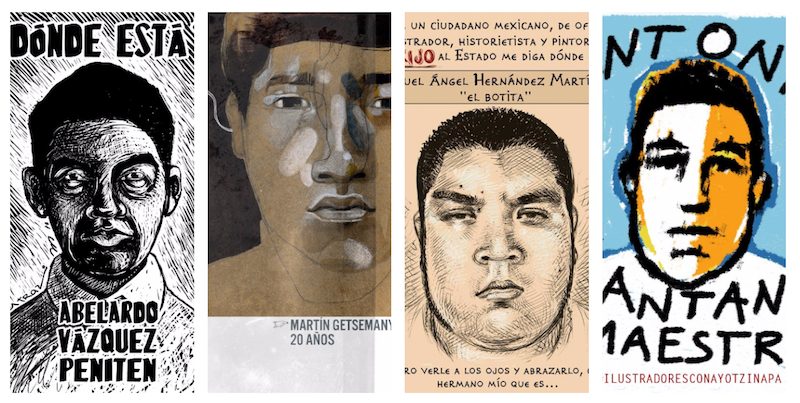

One of the objectives of the seminar, based to a great extent on the books Curating Difficult Knowledge. Violent Pasts in Public Places (2006) and Curatorial Dreams: Critics Imagine Exhibitions (2016), was that each participant would create her/his own “curatorial dream.” This must exhibit some difficult knowledge, even if it was impossible to realize it, either because of material conditions or because the conflict in question was not officially recognized. Due to the recent events in the Mexican municipality of Iguala, I decided to focus on the forced disappearance of 43 students from Ayotiznapa’s Normal Rural School, the night of September 26th, 2014, as well as the murder of some of their classmates and several unlucky passers-by. One of the murdered students was Julio César Mondragón Fuentes; his faceless body was found the next day by the Mexican army, with clear signs of torture. A second autopsy, made two years later, revealed 64 fractures in 40 bones, including the skull, face, and spine, although the commission in charge claimed that the skin of his face was not ripped away by his killers, as it had been claimed, but by scavengers. He must have suffered a lot during his last living moments.

Although at the beginning of the seminar it was stipulated that there would not be an exhibition, the process motivated Lehrer to propose one at the end of the term at Concordia’s Centre for Ethnographic Research and Exhibition in the Aftermath of Violence (CEREV), which would document each participant’s curatorial process. Works would engage into a dialogue with each other, just as when discussions unfolded from diverging perspectives and points of view each week during the seminar.

A student strike at Concordia by the end of the term, in May 2015, interrupted this curatorial process. In light of the political effervescence, the most intense in Quebec since the 2012 student movement known as “The Maple Spring,” my curatorial dream, focused on a highly vulnerable student group in Mexico (rural normal schools), could have contributed to a dialogue on student movements, social agency and the right to dissent in North and Latin America. Quebec students have historically had a huge impact on their society. If tuition fees in the province are among the lowest in North America, it is mainly due to post-68 student protests, anti-racist movements and pro-sovereign groups. So what could Quebec students learn from the history of the 43 missing students? First of all, that protesting strategies usually deployed (demonstrations, strikes, boycotts, occupations) do not necessarily result in real, concrete transformations in the Realpolitik. This does not mean that the right to dissent must not be defended at all costs, mostly in the face of the potential dissipation of the students’ agency due to major global shifts, like neoliberal economic austerity programs, or global warming. Second, analyzing how student protests are treated in similar ways both in Mexico and Quebec helps us understand how neocolonialist strategies, which previously were only applied to ex-colonies or developing nations, are now also perpetrated within developed nations.

Due to the student movement’s social and emotional fluxes, in which I myself was immersed, my curatorial dream kept on being just a project. During that compulsory rest I have realized I did not want to “create” a new work concerning Ayotzinapa, but to channel critical views towards other artists that were engaged in creative practices in a moment of confusion and pain. While on is curating difficult knowledge, it is inevitable to wonder about curatorial responsibility for the exhibition’s theme. As Marianne Hirsch says,

“What do we owe the victims? How can we best carry their stories forward without appropriating them, without unduly calling attention to ourselves, and without, in turn, having our own stories displaced by them? How are we implicated in the crimes? Can the memory of genocide be transformed into action and resistance?”

From the perspective of Mexico’s recent history we can add some other questions like, how should we grasp Mexico’s conflict (be it genocide, a civil war, or a “narco-war”) if it is not recognized as a conflict, if there is not an official mechanism to engage the damage done? How can we understand the long-term implications of this act, and its continuity with previous events, from which the Tlatelolco massacre is just one instance? What is the name of the Mexican conflict, apart from euphemisms like “the struggle against drug trafficking”? How do we enunciate what we do not know how to call?

There is an insurmountable distance between a traumatic experience and its commemoration. Hirsch notices that survivors of the Shoah have an indexical relationship with their memories (that is to say, they refer to embodied experiences), whereas their children interact with them in a rather symbolic way. Through artistic commemoration of an event whose outcome is unknown, we face the challenge of curating with and from uncertainty itself. For most of us, our recalls of the facts are symbolic. Only their murderers, and perhaps the students themselves, know their final destination. Even their relatives get to grasp the event only in a symbolic way. They perceive the absence and only in that sense is their experience indexical. Any kind of certainty has been refused to them beforehand. Moreover, losing the right to know the truth implies a de facto triumph of impunity. Not knowing what happened to them contributes to keeping intact the structural causes behind this attack.

There are no clarifying conclusions, neither in the Ayotzinapa case nor in my curatorial project. In this article I wrote about liabilities in events that the current Mexican government utterly denies. About individual and social processes that bring about public demonstrations, or artistic creations, in the face of traumatic events or violations of any kind of basic human rights (be it in Mexico, Colombia, or Quebec). I wrote about images that hurt, algorithms that will never find the people they are programmed to look for, and which barely give us a certain level of confidence. I wrote about curation as a regenerative process, based on the etymology of curare in Latin—to heal. It is not about exposing wounds to keep them open, though in order to let them heal they must get some fresh air. We have to let them breathe.