The New Storytellers Symposium: Three Vignettes in Search of Human Connection

Nadine Blumer

January 2016

I. A Better World via the “Virtual Reality Empathy Machine.”

“How Virtual Reality (VR) Can Create the Ultimate Empathy Machine” is the title of a TED talk first broadcast in March 2015. It has generated more than 1.2 million views in its first months online. The speaker, interactive media artist Chris Milk, prophetically describes how the immersive quality of VR not only transports viewers into another world, but also effectively alters perceptions and may even change the world. VR is a “machine,” he declares, through which “we become more compassionate, we become more empathetic, and we become more connected. And ultimately, we become more human.”

Milk gives the example of the UN-funded VR film, “Clouds Over Sidra,” which was shown to delegates at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland in January 2015. This film takes viewers into a Syrian refugee camp in Jordan through the eyes of a 12-year old girl named Sidra. As Milk explains, “When you look down, you’re sitting on the same ground that she’s sitting on. And because of that, you feel her humanity in a deeper way. You empathize with her in a deeper way. And I think that we can change minds with this machine.”[i]

Interactive Digital Media. Immersive Participatory Storytelling. Virtual Reality. Empathy. These were the key themes of a one-day symposium, The New Storytellers, held on September 23rd, 2015 at Montreal’s Centre Phi. Speakers included an impressive array of sound and visual artists, journalists, and documentary filmmakers working at the interface of art and new media technologies. They presented innovative, thoughtful and even poignant online digital projects, like Montreal-based AATOAA studio’s philosophical adventure VR game, Way To Go; Or, The Portals Project, which links up people as far apart as D.C. and Tehran in private (digitally mediated) face-to-face conversation; and Hollow, an interactive online documentary film about rural America that transforms viewers into participants as they control the direction the film’s narrative takes. With enthusiasm and optimism similar to that of Chris Milk, speakers extolled the humanistic and democratic potential of immersive, interactive, and participatory media for telling stories – an activity as old as humankind.

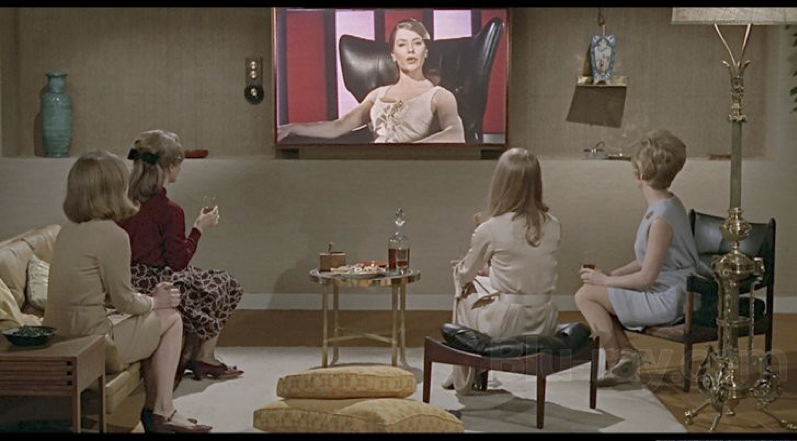

But what do human connection and empathy mean in the digital age? As VR sets become more accessible to the general public (image 1), will companies attempt to sell empathy as part of the VR experience? And what are the ethics of thematizing human suffering as a vehicle for some greater understanding… or, even entertainment?

Image 1. Google Cardboard, a simple DIY viewfinder that attaches to a Smartphone for access to VR technology, runs for about $15 USD

Take for example the recent project from French media design students, [8:46], which developers describe as “a narrative driven experience designed for virtual reality, which makes you embody an office worker in the North Tower of the World Trade Center during the 9/11 events.”[ii] Yes, the purpose here is to experience “exactly” what it was like to be attacked by terrorist hijackers as you hurl yourself off of history’s most famous burning skyscraper (image 2).

Image 2. Still of the VR game [8:46] that creates an immersive experience of 9/11 from within the World Trade Center on the morning of the attacks.[iii]

Or, the interactive game, Playing History 2: Slave Trade, where players travel back in time in the role of a young slave steward working on a trans-Atlantic ship en route to the Americas (image 3). The game’s objective is to “take part in history, within a living breathing world. This kind of interaction is a unique learning method, which encourages the player to relate to the world and actively seek out knowledge.”[iv]

Image 3. Homepage of Playing History 2 – Slave Trade.[v]

Although titled Playing History, this game does little to actually situate the narrative in the historical context of colonization or its legacy, or to explain how or why racial inequality and oppression persist. Instead, the game looks and sounds like the most basic of quest stories (“Join Tim [the slave] and his sister on an adventure like no other!”). Such immersive experiences do not generate human connection or understanding as much as they trivialize sensitive subjects and objectify or sensationalize other people’s suffering – and possibly even traumatize its users.[vi] This is what education scholar Megan Boler calls “passive empathy,” which refers to over-identification that is based on consuming the “other.” It also suggests that such immersive forms of storytelling likely fail to provide concrete, realistic ways for people to transform empathy, that sense of “human connection,” into social action or justice.[vii] As Boler astutely points out, “these ‘others’ whose lives we imagine, don’t want empathy, they want justice.”[viii]

Where then, as Chris Milk promises, is the potential to “change the world” in these immersive experiences? What does it say about humanity if we need a machine to “become more human”?[ix]

II. When Machines Are In Charge: Human Life on the Internet

In his keynote address at The New Storytellers symposium, multimedia artist and computer scientist Jonathan Harris addressed these very questions, introducing ambivalence to the discussion as he talked about his latest online project, Network Effect: Human Life on the Internet. What was initially intended as a project about the beauty of human interconnectedness made possible by the online world eventually transformed into a critique of the web as a space of isolation, social detachment, unmanageable emotion, and even addiction. For anyone who spends time online, there is nothing revolutionary about these ideas. But Harris, and his co-creator Greg Hochmuth, decided to take their malaise to the next level by digitally representing the contrived sense of global interconnectedness that people experience online (ironically, communicating their message by using the very medium they are criticising). Launched this past October, Network Effect is an aggregate of 10,000 YouTube clips and related audio bites, organized around 100 categories of human behaviours that are commonly documented online, such as falling, kissing, eating, vomiting, swimming, sneezing, sleeping, and so on (image 4). The result is an overwhelming, voyeuristic and very loud pastiche of sound and video images culled from across the web and supplemented by endless amounts of user data, tweets, news clips, and consumer brands related to these behaviours.[x]

Image 4. Still of “Shower,” one of the categories in Harris and Hochmuth’s Network Effect.[xi]

Network Effect shows us how absurd, distracting and even dehumanizing our obsession with data is; and how the Internet, says Harris, “steals beauty from our lives.” The website’s epilogue explains that,

We do not go away happier, more nourished, and wiser, but ever more anxious, distracted, and numb… ‘Keep searching and you will discover,’ these services seem to proclaim, but the deepest truths cannot be found by searching — and you will not find them in data, in videos, or in images of other people’s lives.[xii]

So, where might we find these “deepest truths”? In his presentation, Harris explained the trajectory of his own career—from a regular canvas and paint artist to a computer-based digital artist—and how the idea of Network Effect emerged from his increasingly isolating experience of working online. But it was not until he stopped one day to re-read a printed copy of a poem tacked to his fridge that he found a way of putting words and structure to these feelings. The poem, “What The Living Do” by New York State poet laureate Marie Howe is addressed to her dead brother and is about the banalities of everyday life, of “what the living do.” In a mere 30 lines, the reader is presented with a personal memorial created by a poet for her brother who died of AIDS-related complications and is also reminded of the complexity of emotions that guide us through everyday life. Harris unhurriedly recited this poem to the audience, framing it as his “aha moment” of inspiration after two years of blocked creativity which ultimately led to the creation of Network Effect. The poem, he explained, evoked in him those feelings of alienation and loss of human connection that so many of us experience online.

Harris’ choice to use the Web in order to communicate his message about the dangers of the very medium he is criticizing leaves us with no easy answers but does remind us of the beauty and power of the printed word and poetry in particular.

III. In Praise Of The Printed Word: Dystopian Fears In The Age Of Technology

In 1953, eight years following defeat of the Nazi dictatorship, Ray Bradbury published the now classic Fahrenheit 451. In this dystopian novel, Bradbury imagines a techno-centric society in the near future where all reading materials have been banned. The written word, it is believed, exposes the reader to a wide range of human emotion and thus, goes the logic of Bradbury’s authoritarian society, revolt and disobedience to the state will follow.

The title, Fahrenheit 451, is the name of this society’s Fire Brigade and refers to the optimal temperature at which paper burns. Fire fighters are the heroes here, responsible for seeking out and then (publically) burning any remaining books that have not already been destroyed. In lieu of reading, people are encouraged to self-medicate with pills and to spend time with “The Family,” the euphemistic name given to the large-screen television sets in every home that distribute mindless state-run programming (image 5).

In Francois Truffaut’s 1966 adaptation of the novel, he depicts this society of dulled emotion, rote knowledge, and lack of human interaction by showing us how new technologies have pushed people to narcissistic extremes (narcissism being the opposite of empathy). Throughout the film we see individuals relying on their own touch in order to experience a fleeting moment of human connection: they silently hug their own bodies, lovingly pet a fur coat collar, kiss their own skin, or caress strands of their hair (image 6).

Denied a lexicon of emotion, these individuals are practically immaterial, divorced from imagination, a connection to themselves and others, and the experience and feel of everyday life. In the film adaptation, a group of rebellious characters that lives on the margins of this society bands together in an innovative scheme to preserve the written word. Prohibited from having physical books, they memorize full manuscripts and thus, literally come to embody the words of poetry and literature otherwise denied them and subsequent generations.

How does all of this relate back to Chris Milk’s praise of VR and the promise of a “changed world”? Or, Jonathan Harris’ simultaneous critique of and ongoing experimentation with Web technologies? To be sure, every generation’s technological innovations have incited fear while also contributing in some way to an improved quality of life. There is no question that our own advances with digital media offer an exciting new toolkit for telling stories of all kinds, for maintaining old connections while also creating new ones (in virtual and in physical space), for raising awareness, and yes, perhaps even for inciting profound forms of social justice action. But what are we possibly overlooking or losing in the process of “digitizing” the stories we tell? How might we be at risk of commodifying emotion, turning empathy into a consumer good and ultimately, numbing ourselves to human connection and justice?

For me, the search for beauty, understanding, and human connection begins with these questions and resides in a kind of ambivalent space, somewhere between the dusty pages of old books and the shiny promise of digital and virtual connectivity.

Epilogue

i Excerpt from Chris Milk’s Ted Talk, March 2015. https://www.ted.com/talks/chris_milk_how_virtual_reality_can_create_the_ultimate_empathy_machine?la nguage=en

ii As cited on official webpage of [8:46], http://www.08h46.com/

iii Photo source: http://www.theverge.com/2015/10/30/9642790/virtual-reality-9-11-experience-empathy

iv http://store.steampowered.com/app/386870/

v http://store.steampowered.com/app/386870/

vi An earlier version of the Slave Trade 2 game included a section called, “Slave Tetris” in which players

were given the challenge of stacking captured slave bodies into the cargo of the ship, Tetris-style. Serious

Games Interactive, the Danish company responsible for the game, removed this section in response to social media backlash. The broader ethical questions surrounding the gamification of serious issues is a complex subject that I am exploring elsewhere. There are however a slew of excellent and thoughtful examples of games (not necessarily VR-based) that manage to respectfully deal with the complexities of violent histories or other sensitive and difficult issues (e.g. Syrian Journey: Plan Your Escape Route; Papers, Please; and The Oldest Game which is currently in development at Concordia University).

vii Megan Boler, 1997, “The Risks of Empathy: Interrogating Multiculturalism’s Gaze,” Cultural Studies 11(2): 253-73.

viii Boler, p. 255

ix Excerpt from Chris Milk’s Ted Talk, March 2015. https://www.ted.com/talks/chris_milk_how_virtual_reality_can_create_the_ultimate_empathy_machine?la nguage=en

x Harris hired workers from Amazon Mechanical Turk to amass the images/sound bites, paying them $0.25 per video.

xi Photo Source: http://www.wired.com/2015/10/voyeuristic-site-will-make-reconsider-social-media/

xii http://networkeffect.io/epilogue

xiii Photo Source: http://www.blu-ray.com/movies/Fahrenheit-451-Blu-ray/77298/

xiv Photo Source: http://lecinemadreams.blogspot.ca/2013_04_01_archive.html

xv Thanks to Shannon Fogg-Menand from the Missouri University of Science and Technology for tracking down a physical copy of Marie Howe’s book and scanning her poem for me. At each of Montreal’s four university libraries and its Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ), I was only able to find an electronic version (!) of the book.